I Think, Fast and Slow

Introduction

Often times we swiftly come to conclusions or decisions, without being aware that

- we are making a big mistake based on the information that is available,

- we are looking for our fondest beliefs to be true, or worse

- we are being manipulated !

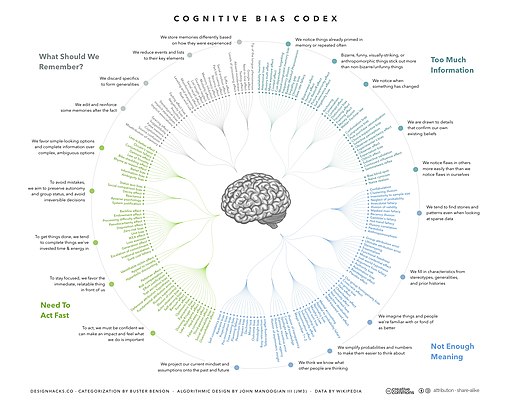

Hence, one of the important points of view we need to retain is to be aware of our Cognitive Biases. Being aware of this may be the first step to check ourselves and therefore arrive a more nuanced “appreciation of the situation”, that would then allow us to formulate our Innovative Problems better.

Let us now engage in some simple activities that show off! to us, our Cognitive Biases!

Some Simple Cognitive Bias Games

Bias #1: Cognitive Miserliness

Game

Let us start with a set of relatively easy games. Here PDF are some questions for you. Please write or call out the answers as you see them.

Interpretation

References for Further Reading

TBF!

Bias #2 Halo Effect

Game

Look at the set of words given here PDF. We have a set of words arranged in a series; each word-set describing a person. Please look at these and then write a brief description of that person.

Let us now compare what different people wrote about the persons described the respective word-sets.

Interpretation

What we saw was that the word-set are the same but in reverse order. The SEQUENCE in which we encounter them colours our opinion of the person whom they describe. So first impressions do seem to be last impressions! This is a Cognitive Bias the Halo Effect at work. We formulate decisions based on first impressions. What can we do to over come this bias?

References for Further Reading

Bias #3 Priming

Game

You will be given a small questionnaire PDF, with a single multiple-choice question. Please enter your answer at the appropriate location.

Intepretation

The Marvels of Priming

As is common in science, the first big breakthrough in our understanding of the mechanism of association was an improvement in a method of measurement. Until a few decades ago, the only way to study associations was to ask many people questions such as, “What is the first word that comes to your mind when you hear the word DAY?” The researchers tallied the frequency of responses, such as “night,” “sunny,” or “long.” In the 1980s, psychologists discovered that exposure to a word causes immediate and measurable changes in the ease with which many related words can be evoked. If you have recently seen or heard the word EAT, you are temporarily more likely to complete the word fragment SO_P as SOUP than as SOAP. The opposite would happen, of course, if you had just seen WASH. We call this a priming effect and say that the idea of EAT primes the idea of SOUP, and that WASH primes SOAP.

Priming effects take many forms. If the idea of EAT is currently on your mind (whether or not you are conscious of it), you will be quicker than usual to recognize the word SOUP when it is spoken in a whisper or presented in a blurry font. And of course you are primed not only for the idea of soup but also for a multitude of food-related ideas, including fork, hungry, fat, diet, and cookie. If for your most recent meal you sat at a wobbly restaurant table, you will be primed for wobbly as well. Furthermore, the primed ideas have some ability to prime other ideas, although more weakly. Like ripples on a pond, activation spreads through a small part of the vast network of associated ideas. The mapping of these ripples is now one of the most exciting pursuits in psychological research.

The Ideomotor Effect Another major advance in our understanding of memory was the discovery that priming is not restricted to concepts and words. You cannot know this from conscious experience, of course, but you must accept the alien idea that your actions and your emotions can be primed by events of which you are not even aware.

In an experiment that became an instant classic, the psychologist John Bargh and his collaborators asked students at New York University — most aged eighteen to twentytwo — to assemble four-word sentences from a set of five words (for example, “finds he it yellow instantly”). For one group of students, half the scrambled sentences contained words associated with the elderly, such as Florida, forgetful, bald, gray, or wrinkle. When they had completed that task, the young participants were sent out to do another experiment in an office down the hall. That short walk was what the experiment was about. The researchers unobtrusively measured the time it took people to get from one end of the corridor to the other. As Bargh had predicted, the young people who had fashioned a sentence from words with an elderly theme walked down the hallway significantly more slowly than the others.

References for Further Reading

TBF!

Wait, But Why?

As Kahneman says, it is good to be wise about our biases. There are ways in which one can be aware of them and try to overcome them, by say taking time and not opting for the first answer that your mind suggests, and doing some counter-factual thinking (“What if this is NOT the answer?”).

Doing so will allow us to gather research information better, ask better questions and arrive at better inferences as to the problem that we might be trying to articulate.

References

- Kahneman, Daniel. “Thinking Fast and Slow”

- Benson, Nigel C.; Ginsburg, Joannah; Grand, Voula; Lazyan, Merrin & Weeks, Marcus; Collin, Catherine, “The Psychology Handbook: Big Ideas Simply Explained”

- Pashler, Harold. “Encyclopedia of the Mind”

- Holyoak, Keith J.& Morrison, Robert G., “The Cambridge Handbook of Thinking and Reasoning”

- Quality Enhancement Program (QEP cafe) https://sites.google.com/site/qepcafe/#training-modules